In 2009, a friend and I were living in Japan. That year, we learned that it was possible to get to Hashima, commonly called “Battleship Island”, albeit highly illegal.

We did it anyways.

Podcast Sponsor: Get a FREE audiobook and 14-day trial today by signing up at www.audiblepodcast.com/weirdworm

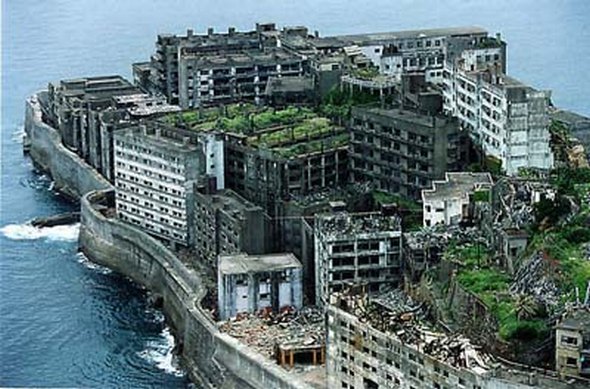

We had heard of Battleship Island (in Japanese, Gunkanjima) before ever coming to Nagasaki, but had never considered sneaking onto the ghost island. It had been closed since the 1970’s, and now sat off the coast of Nagasaki City, quiet and haunting. Going there is supposedly punishable by a one month stay in a Japanese prison as well as deportation. We have never considered the possibility, though there was something romantic and adventurous about the notion. This changed one week, when in a conversation with others in the area we learned that some people had gone and gotten away with it. It wasn’t even difficult, they told us. Suddenly, the forbidden fruit of the Ghost Island seemed just within grasp, and we knew we wanted to try.

The easiest way to sneak into Hashima, we were told, is to go to the closest neighboring island, Takashima. From Takashima, you pay someone with a boat to ferry you over and look the other way. We decided to go for it.

We left from Nagasaki City early in the morning on a ferry bound for Takashima, and sipped coffees leisurely during the hour-long boat ride. Takashima itself is largely unremarkable (especially in comparison to its neighbor), but its story in many ways mirrors that of Hashima:

Like Hashima, Takashima’s history is defined by coal mining. For centuries, Takashima’s inhabitants were said to have gathered coal from exposed rock beds along the shore, and in the eighteenth century began exporting it. Over time, Takashima’s mining system became an enormous success, and the island settlement grew. At the height of its production, the island’s inhabitants numbered around 20,000. The population of Takashima has now dropped to about 600, the majority of whom live in one large apartment complex on the center of the island. A scattered constellation of old houses surrounds it, and beyond that are the vestigial remains of what was once a vibrant community – a tennis court with no nets, the pavement cracked and stained, a basketball goal bent by wind and time, decaying picnic tables. There are overgrown forested areas as well, home to indigenous wild hemp, we learned from a sign near the port.

We were greeted by a particularly suspicious police officer as soon as we stepped off the boat. He asked to see our Foreigner Registration Cards, and then took down our information. When he asked why we’d come to the island, we told him we were interested in taking pictures. He told us it took approximately an hour to walk around the island, and that he’d wait for us at the docks. He clearly didn’t believe we’d traveled so far out of the way just to kill an afternoon looking at an island not very different from any of the others in Nagasaki. His suspicions were not unreasonable. After all, Takashima is extremely close to Hashima, and it is also an abundant source of naturally growing marijuana. There isn’t much reason to visit Takashima if you’re not interested in either of things, both of which are illegal. Still, we were undeterred, and after some pleasantries made our way to the far side of the island to seek out a fisherman to bribe.

We soon found a boat owner who would take us to Hashima in exchange for a little cash and a cooler of cheap beer. We happily accepted the deal, and after a brief run to the island’s only convenience store, a six-pack in tow, we ran back to the pier.

The water was calm and blue, and surrounding Battleship Island were several fishing boats. Occasionally, flying fish broke the surface of the water, gliding along the waves. Hashima is surrounded by a large concrete sea wall to protect the buildings from rising tides and large waves, and even from Takashima we could see people sitting atop it, casting their fishing line into the sea. Our boat driver told us that fisherman are allowed to go to the island, but they’re only allowed to sit on the wall to fish; going deeper into the maze of forgotten buildings was deemed too dangerous to allow. Furthermore, he didn’t want to take us on shore. We offered a compromise: we’d say we were there to fish. The problem with this was that we didn’t have fishing licenses. Once again, we tried to sidestep this inconvenience, asking if we could get fishing permits for the day, intending to slip off of the wall and disappear on our own. He made a phone call, but the port authority wasn’t interested in giving us permits for the day. We circled the island for a while, taking pictures from the boat, and after a lengthy discussion about the history of the island he decided to drop us there after all.