Even great men make mistakes. We know this as common sense, but there’s a difference between someone missing a pass and someone leading thousands of men to their graves. Mistakes on the battlefield are costly, and seem even more so when committed by otherwise brilliant men.

1.

Sir Douglas Haig

The Man:

A general for the British forces during World War I. He’s most notably a knight (which will seem baffling to you in a moment, we’re sure) and was Commander of the British forces during the Battle of the Somme in France in 1916, where his military fumble would occur.

The Mistake:

And by fumble we mean overseeing the single largest loss of British life in modern history.

Yikes.

The German army had invaded France in August 1914 and controlled large parts of the country. A combination of French and British forces planned to meet and push the Germans back while reclaiming various towns and other strategic locations. Haig’s men lead the offensive with an apparent mindset for attrition. In the end, however, things didn’t go quite his way; British forces lost over six-hundred thousand men – twenty percent of their active army – between July and November when fighting ceased. To put that number in perspective, that’s over half their total casualties of the war. Despite much of his force being reduced to corpses, Haig called it a success.

But was it really? Most folks say “no” because in the end he was only able to penetrate German territory by about six miles and captured zero towns. Haig was criticized for his handling of the conflict, but to be fair to him luck wasn’t exactly on his side. He debuted the tank during this battle but many were rendered useless by mechanical breakdowns.

2.

Gunichi Mikawa

The Man:

Hot-shot Japanese naval commander during World War II. His career, however, is a bit of a mixed bag in terms of general success. Coincidentally, what was arguably his greatest success happens to be his greatest failure.

He’s always staring. Just… staring.

The Mistake:

While commanding a force of heavy cruisers and one destroyer in the Pacific, Mikawa set his sights on the Solomon Islands, a key position for Allied forces. Early in the morning of August 9th, 1942, Mikawa gave the order to his ships to open fire on US Navy ships stationed there. In a single morning they sank most of the enemy ships (including a Royal Australian Navy cruiser) without losing a single ship, let alone life. Then, with the Allied ships on the ropes, Mikawa called it a day.

It was a decision based seemingly on sound logic: Mikawa’s ships were scattered and needed to reload torpedoes. Regrouping and reloading would have taken a great deal of time. Moreover, he knew that the heavy cruiser was no longer in production and any he could potentially lose would have been lost forever. The crux of his decision, however, was the mistaken belief that a US aircraft carrier was in the area and would soon be upon them. Though he was urged by his staff to continue the assault, he returned to his base in the north. Had he continued the setback for the Allies would have been enough to extend fighting up to another year. What’s more, he lost the opportunity to sink several cargo ships that were waiting until day break to deliver supplies to waiting marines, possibly forcing an evacuation of the Solomon Islands entirely.

3.

Philip VI

The Man:

King of France from 1328 until his death in 1350. He most notably tried to invade England during the Hundred Years War, with “tried” being the key word of the sentence.

Even he looks disappointed in himself.

The Mistake:

At first glance the Battle of Crecy should have been in the bag for Philip. His force consisted of thirty-five to one-hundred thousand men, mostly French nobility, compared to the combined Anglo-Welsh forces of fifteen-thousand or so. However, logistics were apparently his undoing. His first charge of knights nearly exhausted themselves after running several miles to the battlefield. To make matters worse, after slogging through the mud they had to run uphill to reach the enemy. Longbow archers had no problem picking them off (the armor of the day offered little protection from such archers).

Go time.

Philip then went forward with a group of mercenary crossbowmen. This too proved to be flop; wet strings and poor distance calculation combined to ensure that their volleys fell short. Meanwhile, the enemy archers only had to advance part way down the hill to start picking them off. The real kicker, however, is when the mercenaries retreated: a second group of knights under Philip’s command charged and slaughtered them. That’s right – soldiers fighting under the same banner willfully killed each other. Despite fifteen more charges, Philip lost the battle.

4.

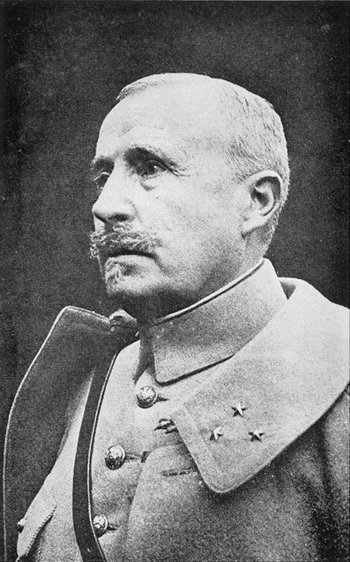

Robert Nivelle

The Man:

A French artillery officer who managed to rise up the ranks to commander-in-chief on the Western Front. He has an offensive named after him, but as you’re about to learn that’s not always a good thing.

The Mistake:

The infamous Nivelle Offensive was a proposed massive assault on the Western Front that would end the war in two days. At least, that’s what Nivelle proposed. He certainly didn’t chance the numbers, bringing one-million men and seven-thousand artillery pieces, including new tanks. Three separate attacks were proposed with Nivelle’s taking place at the heavily fortified Chemin des Dames ridge.

Unfortunately for Nivelle, the Germans had intercepted his plans and had adequate time to prepare. Though French soldiers were able to claim a trench from the enemy, the Germans were employing new machine guns to make quick work of the infantry while blowing the tanks to pieces before they could be of any use. In a game of Risk they rolled triple sixes.

And that’s game.

And you certainly can’t hold that against Nivelle — sometimes you’re simply outclassed. However, as casualty reports came in from the front line he flat our ignored them and sent more men to their deaths. Despite not making any reasonable progress in the assault he sent ninety-six thousand men or more (there’s some debate as to whether or not the number was downplayed) to their deaths. Part of the plan was a link up with Russian and British forces, so he may have kept the fighting going thinking reinforcements were just around the corner, but the Germans knew about that part of the plan too and cut them off before they arrived.

Written by NN – Copyrighted © www.weirdworm.net

Image Sources

Image sources:

- – Sir Douglas Haig: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/70/Douglas_Haig.jpg

- – Gunichi Mikawa: http://ahoy.tk-jk.net/MoreImages/Solomons/GunichiMikawa.jpg

- – Philip VI: http://media.comicvine.com/uploads/0/9241/677981-philippe6devalois_large.jpg http://www.loeser.us/examples/himages/blkprince1.jpg

- – Robert Nivelle: http://4yearsofww1.info/etaples-cemetery.jpg http://4yearsofww1.info/etaples-cemetery.jpg