CPR, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation is a technique used to save people whose heart and lungs have decided to quit by heroically mashing ones hands and face into a person’s face and chest. It’s a hallmark medical system, right up there with the Heimlich maneuver or “Not Applying Leeches for Every Medical Ailment”. And while it can be an important tool in the fight against the icy, relentlessly tightening grip of death, it turns out that, for a number of reasons, you’re still probably going to die.

5.

Resuscitation is Poorly Understood

It doesn’t take a Planned Parenthood security guard to tell you that the point at which human life begins is a little bit of a contentious issue. The point at which we can declare something to be dead is similarly fuzzy. Until the late 1700’s, we tended to go with “did he flinch when poked with a sharp stick?” line of diagnosis.

This all started to change when the Dutch got sick of the stupid bastards who were clogging up their beloved canals. Lacking the necessary 1-900 psychics to ridicule people in the spirit world, they set about developing a system to revive those who’d drowned. The British soon followed with their hilariously named “Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned” which was managed by the even more stereotypically English “Royal Humane Society for the Apparently Dead”. That is totally true, and yes, they did spend more time on politeness than legitimate medical science.

Problem solved!

The methods they developed included bleeding by leeches (naturally), tickling the throat, variations on getting people upside-down and even literally blowing smoke up person’s rectum. Given how that last practice has passed into the common vernacular, you can imagine how well this went over. Fortunately, there was some success with two techniques: pressing down on abdomens and doing respirations. These actually caught on, though the physiology was poorly understood. For example, it took about two hundred years for people to realize that the airways needed to be clear for air to go in them.

Science, circa 1799.

Even after hundreds of years of progress, we’re still trying to figure out the magic formula. There are conferences, research and symposia on the matter. And yet, the jury is still out on the basic concepts of CPR, like the ratio of compressions to breaths, or whether to slam on your fragile organs instead of your heart or even whether to administer mouth-to-mouth at all! Hopefully your would-be savior has kept up to date on the major medical journals.

Also, thanks to science, we’re also doing our best to generate some cutting edge or “wacky” techniques. Therapeutic hypothermia, for example, involves intentionally reducing your temperature to low levels to induce some kind of hibernation or something. We’re not totally sure, but it definitely seems pretty awesome. Not that it will do you much good unless you decide to keel over during the Iditarod.

They probably don’t even have the KFC Doubledown up there. Savages.

4.

The Education is Suspect

We’ve seen it on TV, where someone suddenly flops over and they’re unresponsive but some anonymous hero immediately jumps in with the golden phrase: “Stand back! I know CPR!”. It’s the next best thing to having a real doctor. Or a nurse. Or an EMT. Or a fireman… police officer… the point is, “guy who took a lifesaving class at the Y” is probably in the top ten.

We’d probably trust the dentist more. He deals with mouths every day.

Oh, and lifeguard should be in there somewhere.

Anyway, the idea is that the Average Joe can also be a hero if they simply take part in some rigorous CPR training. Except for the rigorous and the training parts. To truly maintain your certification through the American Red Cross, you need to take a refresher course every year (in most states). That means a fee and more time out of your busy schedule, so you can guess how many people who don’t have to maintain it for their work bother to stay consistently certified. People that let it lapse are also lazier than you might expect. How much class time do you need to prepare you to save lives for an entire 12 months? Only 4 hours, as it turns out.

Retention is a serious problem with any educational experience, but it becomes pretty friggin’ important when the student is responsible for a life. The director of the CPR Subcouncil for the American Red Cross comes right out with it: “Hopefully, you’ll never have to use your CPR skills. But you can’t assume they’ll stay with you for the long haul because people tend to forget them quickly”. That’s why they insist on the annoying recertification that we’re sure absolutely everybody goes through with. As they put it: “You need to get your hands and your mouth on a mannequin every year.”

Actually, maybe that’s not a bad idea.

Turns out people may need to study for longer than a game of major league baseball each year. Within a few weeks of training, most people aren’t able to perform CPR at levels well enough to meet minimum standards. That’s right, unless you get a guy fresh out of class, you’re probably getting sub-par care. And the same facts apply to healthcare professionals too. Doctors who don’t perform it frequently start making lots of mistakes. Not that we can blame the classes for being kind of ineffective. You’d have a hard time too if you had to plant your lips of the mouth of dead French woman who drowned herself. We get the irony or whatever, but that’s seriously creepy.

Should we use a generic face? Naw, why not a death mask instead?

3.

People Don’t Bother to Help

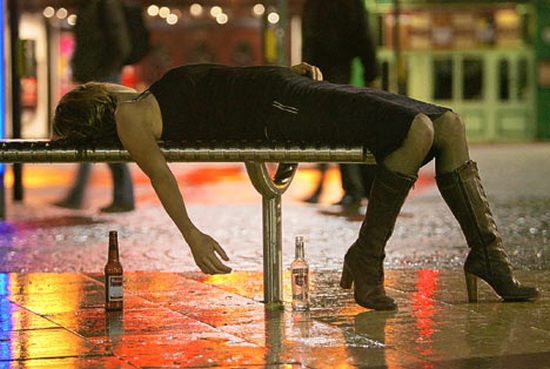

So maybe you keel over from the strain of moving boxes during your weekly soup kitchen volunteer work. Or maybe it’s from a particularly vigorous lapdance. We’re not here to judge your Tuesday evening schedule. The point is; when you’re down and not looking too good, it’d be best to be in a crowded place. If one of those filthy hobos or strippers are going to jump in, having more people around increases the odds that somebody with recent CPR will help, right?

It’s totally not human nature to take pictures for the internet instead of help people right?

Truth is, unless you’re lucky enough to have blown your ticker during a cardiology convention, you might still be in a heap of trouble. The reason is psychology. The well documented “bystander effect” shows that when people witness emergency situations in groups, they’re much less likely to respond. There’s plenty of anedotal evidence of people not helping, like Eleanor Bradley, who fell and broke her leg in the middle of New York City, only to have people step around her for forty minutes before someone stopped to help (probably some hick, er, good Samaritan from Iowa). Now, that’s not to say that only New Yorkers are bad people (though they are), it seems we’re just hardwired to be less responsive when we’re in groups. Among the most ridiculous examples of the phenomenon can be seen in the “Smoke Filled Room” test:

Unfortunately, a situation requiring CPR isn’t like a broken leg. Every minute counts, and you need people to jump in as soon as possible if you’re going to make it. Sadly, bystanders are likely to ignore you or watch for a number of reasons. We tend to look to each other to assess a situation, and this can end up with everyone looking, but nobody doing anything. Sometimes we all just assume someone else will help. Some fear embarrassment, either because they overreacted to the situation or someone more capable will take over. Or some might doubt their ability to help, maybe because they weren’t paying close attention for those four measly hours.

What? Yeah yeah, mayo-provalone resandwication. I got it.

It’s been suggested that the bigger the group, the less likely any one person will step up and respond. So if you have a coronary after too much beer and pretzels at the state fair, by the time someone cares they might just have to skip calling the doctor and go straight to the coroner.