Before we begin, we’d like to reiterate that this list only includes five entries despite the subject matter allowing for many, many more. As such we’ve tried to give it as much variety as possible. Some of these guys are notorious for their beliefs being completely wrong, some for their experiments and some for their unfortunate contributions to the modern world. As such a lot of seemingly obvious choices aren’t on the list. We tried to focus on the folks who didn’t get as much face time in the pages of history. With that out of the way, let’s begin.

1.

Johann Conrad Dippel (1673 – 1734)

Clearly the man did not invent handsome cream.

Johann Conrad Dippel was most notable as a theologian, making enemies and allies throughout Europe for some of his ideas. His notoriety comes from alchemy, which he perused throughout most of his life (as did many others during his lifetime – consider it the “South Beach Diet” of his day).

The invention that bears his name is Dippel’s Oil. Made mostly of bone char but containing blood and other organic bits and pieces, the oil had many practical uses that were overshadowed by its more sinister uses as a non-lethal chemical weapon. Dippel’s Oil was used to poison wells in World War II.

Crossing the line into creepy territory, Dippel wrote extensively about experimenting with deceased animals. He claimed to have concocted potions of various uses through boiling dead animal parts, including the Elixir of Life and a mean to exercise demons. There’s actual documentation of these claims, which has led to popular myth stretching the truth just a tad. Dippel never used human parts in his experiments (that we know of), and while he wrote of his own belief that a soul could be transferred from one host to another, there’s no proof that he actually tried this – though many other doctors did.

2.

Andrew Ure (1778 – 1857)

There’s a bit of (heavily disputed) speculation that Dippel was the inspiration for Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein. This is based on his having stayed in Castle Frankenstein and the whole “boiling cadaver’s limbs” thing, but he doesn’t really seem to fit the bill when it comes to human reanimation.

Enter Andrew Ure, Scottish scholar, chemist and doctor. A popular idea of his day was that electricity was the key to life and could be used to reanimate the dead if used properly. What “properly” meant was open for debate, but for Ure it meant cutting up an executed criminal and shoving electrodes into the incisions before lighting the corpse up like a Christmas tree. Did we mention he had an audience, too? Because that’s kind of important.

In cases of suffocation, drowning or hanging, Ure believed that life could be restored by stimulating the supraorbital nerve (when he did this the body simulated breathing, among other much more violent movements). One of his assistants was kicked by the corpse, sending them to the floor. Ure later described how the deceased’s facial expressions morphed from joy to anguish. Much of the audience had to leave the scene, and at least one guy passed out.

3.

Fritz Haber (1868 – 1934)

Admittedly, Haber’s a controversial choice because despite the more downbeat part of his legacy (which we’ll get into in a moment) he did win the Nobel Peace Prize for the Haber-Bosch Process, a means of producing Nitrogen fertilizer and allowing us to feed many more people than we could before at little cost. That’s pretty handy, so we’ll give the man his due.

Also, he nailed the handsome cream.

But then there’s the whole “chemical warfare” thing. Haber is often referenced to as the father of chemical warfare for spearheading the use of chlorine gas and absorbers for gas masks during World War I, making him directly responsible for countless dead soldiers. Haber himself had no problem with this and believed that it was his duty as a German scientist to develop such weapons during a time of war (despite the gas itself being in violation of The Hague convention of 1907). His family disagreed. His first wife committed suicide with his service revolver, most likely in protest of his developing the gas or having witnessed its early use.

During World War II he fled to England, refusing to work with the Nazis. They were able to refine his work, however, to develop the gas used to execute undesirables during the Holocaust. While that’s not exactly his fault, it’s hard to deny that he got the ball rolling.

4.

Stubbins Ffirth (1784 – 1820)

First, let’s start off by saying that by not experimenting on corpses or creating some of the most notorious weapons in history, Ffirth may very well be the most favorable guy on this list. Second, his big breakthrough, that Yellow Fever was related to the stress of summer heat, was totally incorrect, so he’s got a C average for his overall career.

To prove that Yellow Fever isn’t contagious, Ffirth started rubbing the vomit of infected patients into open wounds on his own body because he had a totally good feeling about this one. When he failed to corpse from this, he moved on to drinking vomit, then other bodily fluids like blood, saliva and urine. He never contracted Yellow Fever, which was all the proof that he needed that it simply wasn’t contagious.

There was one major problem with his experiment, however: all the patients he used to make his vomit-blood-spit-pee potions were late term and no longer contagious. Six decades after Ffirth’s self-experimentation it was learned that Yellow Fever was contagious but had to be injected directly into the bloodstream to be so. The man lucked out but was still completely off the mark.

5.

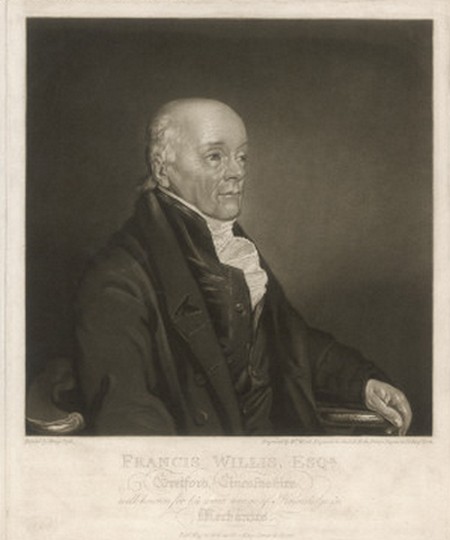

Francis Willis

In the 18th century we didn’t know much about mental illnesses or treating them. There were many alleged solutions to the problem, most of them inhumane, until Francis Willis came along with a solution that was also inhuman but managed to stick thanks to some great PR.

This is what happens when the baby from Eraserhead reaches adulthood.

After turning his home into a sanatorium, Willis would take patients that had been diagnosed with or believed they were suffering from a mental illness. There he would force them to work outside, thinking that the fresh air and physical exercise would help cure them. He also believed that restraint and a certain amount of physical abuse were necessary in the healing process. When King George III went mad, Willis put him in a straightjacket and blistered his skin, just to give you an idea of what we’re talking about, here.

Willis was well respected in his time and his methods seemed to get results. However, it’s very likely that he wasn’t treating mental illnesses as we know them today. What’s more, he opened the door for a sanatorium craze, wherein folks with little to know experience would take on patients simply for profit, corrupting the entire system.

Written by NN – Copyrighted © www.weirdworm.net

Image Sources

Image sources:

- – Johann Conrad Dippel (1673 – 1734): http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_wg49jnGGfvw/TM_ZvnQ9XuI/AAAAAAAAAGA/LKw6Ovcw2ds/s1600/02dippel.jpg

- – Andrew Ure (1778 – 1857): http://www.theglasgowstory.com/images/TGSS00019_m.jpg

- – Fritz Haber (1868 – 1934): http://austradesecure.com/radschool/Vol29/images/Haber.gif

- – Stubbins Ffirth (1784 – 1820): http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-ESMTpwFUpqo/TWGQZcatEKI/AAAAAAAAAO0/e3mk–SQy0Q/s1600/josef-mengele.jpg

- – Francis Willis: http://cache2.artprintimages.com/lrg/45/4528/8WXBG00Z.jpg